A Flag Too Real for the Republic: Art, Censorship, and the Colonial Wound

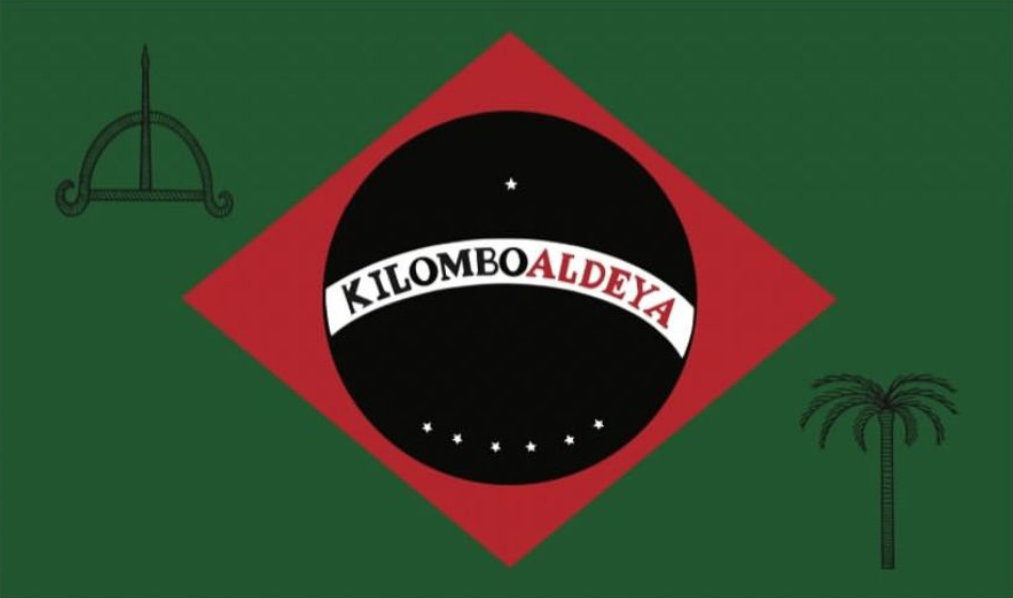

By replacing “Order and Progress” with “KilomboAldeya,” artist Matheus Ribs didn’t just redesign Brazil’s flag—he exposed the fragile scaffolding of the nation’s historical narrative.

There are gestures so simple, yet so politically potent, that they threaten the entire symbolic order. One such gesture came from Matheus Ribs, a Brazilian visual artist whose practice centers on memory, ancestry, and reparation. His works often navigate the intersections of Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous worldviews, confronting the legacy of colonialism with poetic precision and strategic defiance. Ribs isn’t just an artist—he’s a cartographer of silenced histories.

At the SESC Winter Festival in Itaipava, a mountainous and historically elite enclave in Rio de Janeiro, Ribs was invited to exhibit a site-specific installation as part of the Visual Arts program. The piece, titled KilomboAldeya, was a monumental reinterpretation of the Brazilian flag—one that replaced the positivist motto “Ordem e Progresso” with the hybrid word KilomboAldeya, evoking the enduring presence of quilombos (Afro-Brazilian maroon communities) and aldeias (Indigenous villages). It was a powerful visual synthesis of two traditions of resistance historically erased from Brazil’s official imagination.

But within 24 hours, the work was forcibly dismantled by municipal guards. No due process. No consultation. No public explanation. According to Ribs, festival staff were even threatened with arrest. The pretext? A supposed “discharacterization of national heritage.” In short: the flag looked too much like the truth.

The Flag as Battlefield

The Brazilian flag is often mistaken for neutral—green for forests, yellow for gold, stars for states, and a Latin-inspired call to order. But its message was born from empire’s aftershock. When the monarchy was toppled in 1889, the new republic turned to French positivism to manufacture a sense of modernity and cohesion. “Order and Progress” was never inclusive. It was a euphemism for hierarchy, rationalism, and erasure.

By inscribing KilomboAldeya into that space, Ribs wasn’t desecrating a national symbol—he was liberating it. He was declaring that Brazil's foundation wasn’t merely forged in Lisbon palaces and coffee plantations but in the forests of resistance and the villages of continuity. He was inviting us to imagine a country built not on domination, but on the confluence of ancestral strength.

That was enough to summon the state.

Censorship as Continuity

What happened in Itaipava is not isolated. It fits a wider pattern of symbolic policing that has intensified in recent years, particularly under the shadow of rising authoritarianism cloaked in patriotism. Ribs rightly called the incident “an act of police and institutional violence against freedom of expression.”

It’s worth remembering that the region where this censorship took place—the serrana fluminense—is steeped in a plantation legacy. It was built on latifúndios, forged by slavery, and today continues to reflect patterns of exclusion and racialized silence. The state’s intervention, then, wasn’t just about aesthetics. It was a defensive maneuver to protect a version of the nation that erases the very people who built it.

“Public institutions still operate colonial structures to protect symbols of power, but not the bodies and territories historically violated.”

KilomboAldeya Lives

What makes Ribs’s work so resonant is that it refuses to be confined to the gallery or the frame. His practice is deeply situated—rooted in land, in ritual, in ancestral ethics. His interventions are not just visual; they are ontological. They ask what Brazil is, and who gets to define it.

“KilomboAldeya is a living idea”

And indeed, the artwork’s forced removal only extended its reach. It sparked debate, drew attention, and revealed the state’s own nervousness about the symbolic insurgency of those long made invisible.

This is the paradox of censorship: it often amplifies what it seeks to suppress.

In a time when power is allergic to memory and allergic to multiplicity, artists like Matheus Ribs remind us that flags can be more than fabric. They can be mirrors. They can be battle cries. They can be maps toward futures yet to be built.

Because some ideas are too alive to be erased.

Because some symbols refuse to comply.